Tavern Tradition

Design by Alex Povis. Photography by Keith Borgmeyer.

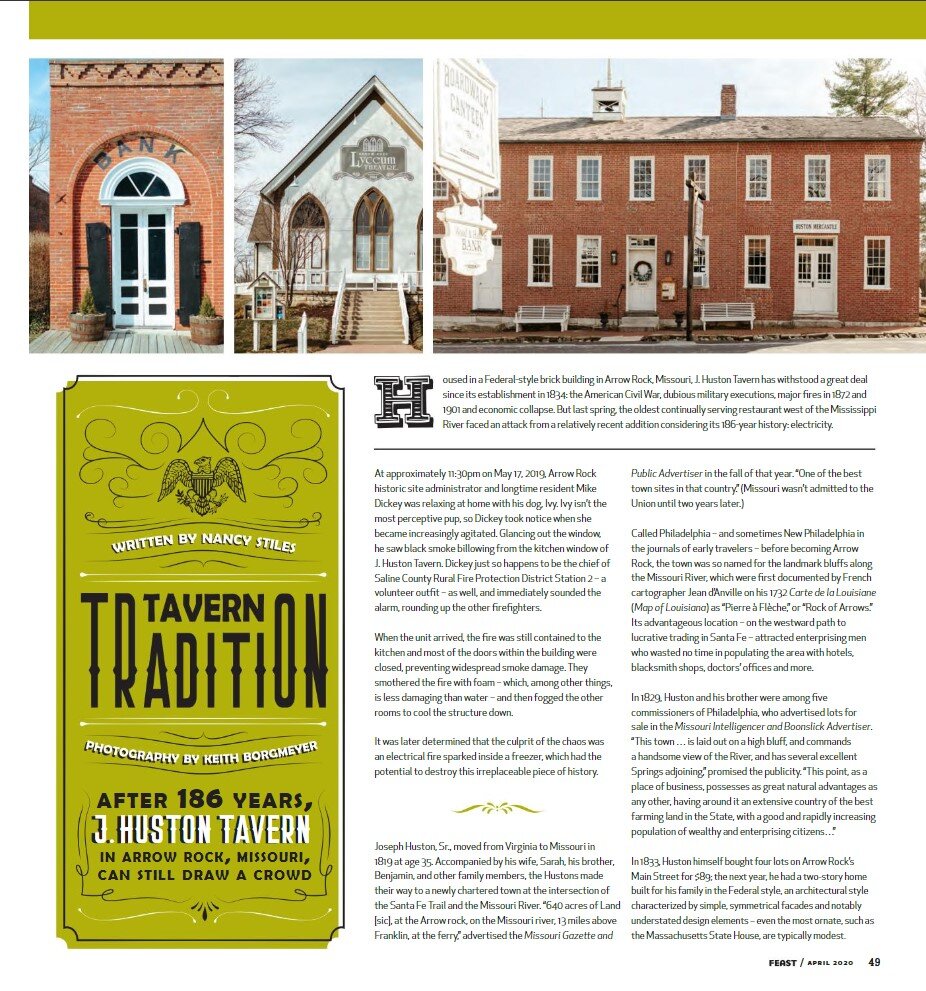

Housed in a Federal-style brick building in Arrow Rock, Missouri, J. Huston Tavern has withstood a great deal since its establishment in 1834: the American Civil War, dubious military executions, major fires in 1872 and 1901 and economic collapse. But last spring, the oldest continually serving restaurant west of the Mississippi River faced an attack from a relatively recent addition considering its 186-year history: electricity.

At approximately 11:30pm on May 17, 2019, Arrow Rock historic site administrator and longtime resident Mike Dickey was relaxing at home with his dog, Ivy. Ivy isn’t the most perceptive pup, so Dickey took notice when she became increasingly agitated. Glancing out the window, he saw black smoke billowing from the kitchen window of J. Huston Tavern. Dickey just so happens to be the chief of Saline County Rural Fire Protection District Station 2 – a volunteer outfit – as well, and immediately sounded the alarm, rounding up the other firefighters.

When the unit arrived, the fire was still contained to the kitchen and most of the doors within the building were closed, preventing widespread smoke damage. They smothered the fire with foam – which, among other things, is less damaging than water – and then fogged the other rooms to cool the structure down.

It was later determined that the culprit of the chaos was an electrical fire sparked inside a freezer, which had the potential to destroy this irreplaceable piece of history.

Joseph Huston, Sr., moved from Virginia to Missouri in 1819 at age 35. Accompanied by his wife, Sarah, his brother, Benjamin, and other family members, the Hustons made their way to a newly chartered town at the intersection of the Santa Fe Trail and the Missouri River. “640 acres of Land [sic], at the Arrow rock, on the Missouri river, 13 miles above Franklin, at the ferry,” advertised the Missouri Gazette and Public Advertiser in the fall of that year. “One of the best town sites in that country.” (Missouri wasn’t admitted to the Union until two years later.)

Called Philadelphia – and sometimes New Philadelphia in the journals of early travelers – before becoming Arrow Rock, the town was so named for the landmark bluffs along the Missouri River, which were first documented by French cartographer Jean d’Anville on his 1732 Carte de la Louisiane (Map of Louisiana) as “Pierre à Flèche,” or “Rock of Arrows.” Its advantageous location – on the westward path to lucrative trading in Santa Fe – attracted enterprising men who wasted no time in populating the area with hotels, blacksmith shops, doctors’ offices and more.

In 1829, Huston and his brother were among five commissioners of Philadelphia, who advertised lots for sale in the Missouri Intelligencer and Boonslick Advertiser. “This town … is laid out on a high bluff, and commands a handsome view of the River, and has several excellent Springs adjoining,” promised the publicity. “This point, as a place of business, possesses as great natural advantages as any other, having around it an extensive country of the best farming land in the State, with a good and rapidly increasing population of wealthy and enterprising citizens…”

In 1833, Huston himself bought four lots on Arrow Rock’s Main Street for $89; the next year, he had a two-story home built for his family in the Federal style, an architectural style characterized by simple, symmetrical, often flat facades, notably understated design elements and geometrical concepts – even the most ornate, such as the Massachusetts State House, are typically modest. The house was constructed by enslaved people using hand-hewn timber and hand-fired bricks.

As traffic through Arrow Rock increased, Huston seized an overt business opportunity: He had the structure expanded on both floors and turned it into a tavern consisting of a restaurant, general store and meeting house. It even had a post office, and Huston was appointed postmaster general in 1845. In 1840, he also added a ballroom, which served as a makeshift hospital during cholera epidemics.

Huston’s establishment was a welcome sight for weary travelers in need of a hot meal and a place to rest their head. “On my first visit to Saline [County], in 1840, I landed at Arrow Rock from a steam boat in the night,” wrote one such traveler, Dr. Glenn C. Hardeman, “and, as I intended going to the country in the morning, I took lodging only at the hotel kept by that well known and popular citizen, Joseph Huston, Sr., for which I was charged the sum of twelve and one-half cents, or, should I say, a ‘bit.’ On my return in a few days I dined at the same hotel and was charged another ‘bit’ for an excellent dinner.”

Like many historic buildings, J. Huston Tavern has its fair share of ghost stories. Friends of Arrow Rock president Chet Breitwieser and executive director Sandy Selby often tell the story of the Lady in White. On a snowy night, shortly after giving birth, a woman who is believed to have been a tailor’s wife rose from bed and walked barefoot out of the tavern. Her footprints were tracked to a nearby bluff, and she was never seen again – except by several tourists who swear they’ve spotted her ghost inside the tavern.